The odds of the U.S. avoiding both a recession and inflation for the next four or five years are small. So it’s safe to say the Fed will intervene in markets again if either of those outcomes emerges.

This raises the question of potential cooperation or conflict between the Fed and the White House, or more specifically, between Janet Yellen and Donald Trump in the new year. Initial indications are that this relationship is more likely to be one of conflict than cooperation.

This is a danger sign for markets and investors.

The Yellen-Trump relationship got off to a rocky start during the presidential campaign when Trump claimed Yellen was keeping interest rates artificially low in order to pump up the stock market and help elect Hillary Clinton. Trump also proclaimed he would fire Yellen as Fed Chair if elected president.

This returns to one of the myths of modern central banking, which is the belief that central banks are independent of political influence. That’s nonsense.

Central banks read the headlines just like everyone else, and they have their political preferences; they just won’t admit it. Janet Yellen held the U.S. policy rate to near zero in September and November 2016 to help the Democrats’ chances in the election.

Once the Republicans won, she raised rates in December 2016 and is set to raise them again in March 2017. That’s a head wind for the stimulus plans of the new Trump administration, and is an example of central banks meddling in politics.

Of course, Trump has no power to fire Yellen but his disfavor with her policies was clear nonetheless. It’s also worth pointing out that Trump may get to appoint as many as four members of the Fed board of governors in the next year.

Trump has also called for the adoption of “rule-based” Fed policy making.

The leading rule is the Taylor Rule, named after economist John Taylor of Stanford University. The Taylor Rule is essentially a suggested guideline for central banks to respond to changes in economic conditions. It’s supposed to allow for shorter-term economic stability, while still maintaining longer-term growth.

Current application of the Taylor Rule would result in a Fed funds rate of about 2.5% versus the current rate of 0.5%. The objective nature of the Taylor Rule lent credence to Trump’s claim that Yellen was keeping rates low to help Democrats.

At her press conference on Wednesday, Dec. 14 following the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting to raise rates, Yellen struck back at Trump. She was implicitly critical of Trump’s indicated fiscal policy proposals.

Yellen said she favors use of fiscal policy, basically tax cuts and increased government spending that expands productive capacity and productivity in general. This includes expenditures or tax credits for education, worker training and certain infrastructure.

Yellen implicitly disfavored Trump’s across-the-board tax cuts that benefit the wealthy who have a low marginal propensity to consume without doing much to expand output. Yellen said she would reserve judgment on Trump’s infrastructure spending plans until details are announced.

Yellen also threw down the gauntlet at Trump by indicating she might remain on the Board of Governors even if she is not reappointed as Chairman. This is possible because a Chair has a four-year term, while a governor has a 14-year term. Yellen’s term as Chairman expires in January 2018, but her term as governor does not expire until 2028.

Even if Trump announces a replacement for Yellen as Chair this time next year, she could stay on the board and be a thorn in Trump’s side for the remainder of Trump’s term as president. That would also deprive Trump of the ability to fill her seat with a more friendly appointment.

This combination of Yellen’s implicit willingness to remain on the board after 2018, and her disfavor of Trump’s tax cuts for the rich sets up a confrontation between the Fed Chair and the new president that could prove unsettling to markets in the months ahead.

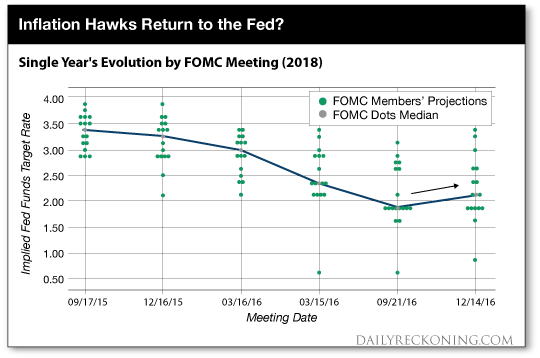

The clearest signal of a coming confrontation between Yellen and Trump was revealed in the “dot plots” of the Fed governors and regional reserve bank presidents shown in the charts below.

The green dots are the forecasts of individual Fed governors and regional presidents. The blue line is the median of these estimates.

The most striking feature of the separate forecasts for 2017 and 2018 is the upward bend in the curve as a result of the Dec. 14, 2016 FOMC meeting. For the first time in years, the forecast indicated an increase relative to prior meetings rather than a decrease.

In particular, the “dot plots” showed a median forecast of three interest rate hikes in 2017 versus the prior expectation of two hikes. Fed officials expect Trump’s reflation policies to produce higher nominal growth, which requires higher nominal rates to avoid inflation.

The significance of this expectation cannot be overstated. It means the Fed has low tolerance for being behind the curve on inflation. It also means that the Fed will probably not be accommodating fiscal policy with helicopter money anytime soon.

In short, the Fed expects to “lean in” against the Trump stimulus and to avoid letting the economy run hot, which just a few months ago she indicated she might.

The Fed is concerned that if another recession started tomorrow, it has limited ability to cut rates. After December’s hike, they still only have about 50 basis points to work with.

They could cut twice to return to zero before they’d have to start talking about negative rates. But the Fed is desperate to raise rates. They want to get rates up to 2 or 3% before the recession starts so they can cut them to get out of the recession.

The question is, how do they raise rates to 2 or 3% without causing the recession they’re trying to prevent?

That’s what I call the Fed’s conundrum, and that’s exactly where the Fed is now. Is this a good time to raise rates? Probably not, but they are going to try to do it anyway.

The problem with the Fed’s assessment is that the Trump policies may not be nearly as stimulative as the Fed expects. Congressional leaders such as Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell have already said they expect Trump tax cuts to be “revenue neutral.”

This means that for every cut in tax rates there must be an offsetting revenue increase from some other source, such as the elimination of tax deductions and credits, conversion of capital gains into ordinary income, repeal of Obamacare, or reductions in entitlements. Trump has already said entitlement cuts are off the table.

Whatever compromise is agreed will greatly reduce the stimulus effect from Trump’s tax policies.

Likewise, Ryan and McConnell have spent years fighting President Obama on spending increases and have used resistance to increases in the U.S. debt ceiling to drive home their opposition.

It will be difficult for Republicans suddenly to become the party of big spending and higher debt ceilings without extensive criticism from the Democrats, the media, and parts of the Republican base. Increased spending is in the cards but it may be far smaller than both Trump and the markets expect.

In short, the Trump “stimulus” may turn out to be far smaller, and far less stimulative than markets currently anticipate. This gap between expected and actual stimulus will be apparent by the spring of 2017.

Regards,

Jim Rickards

No comments:

Post a Comment