Josh Siegel /

German soldiers prepare to deploy to Lithuania

for NATO's Enhanced Forward Presence, a forward deployment to protect

members at risk for a Russian attack. (Photo: Matthias

Balk/dpa/picture-alliance/Newscom)

President Donald Trump alarmed European allies during the

campaign when he suggested he might not defend NATO nations if they

don’t fulfill their financial obligations, but he is not the first U.S.

leader to express concerns that member countries don’t spend enough on

their militaries.

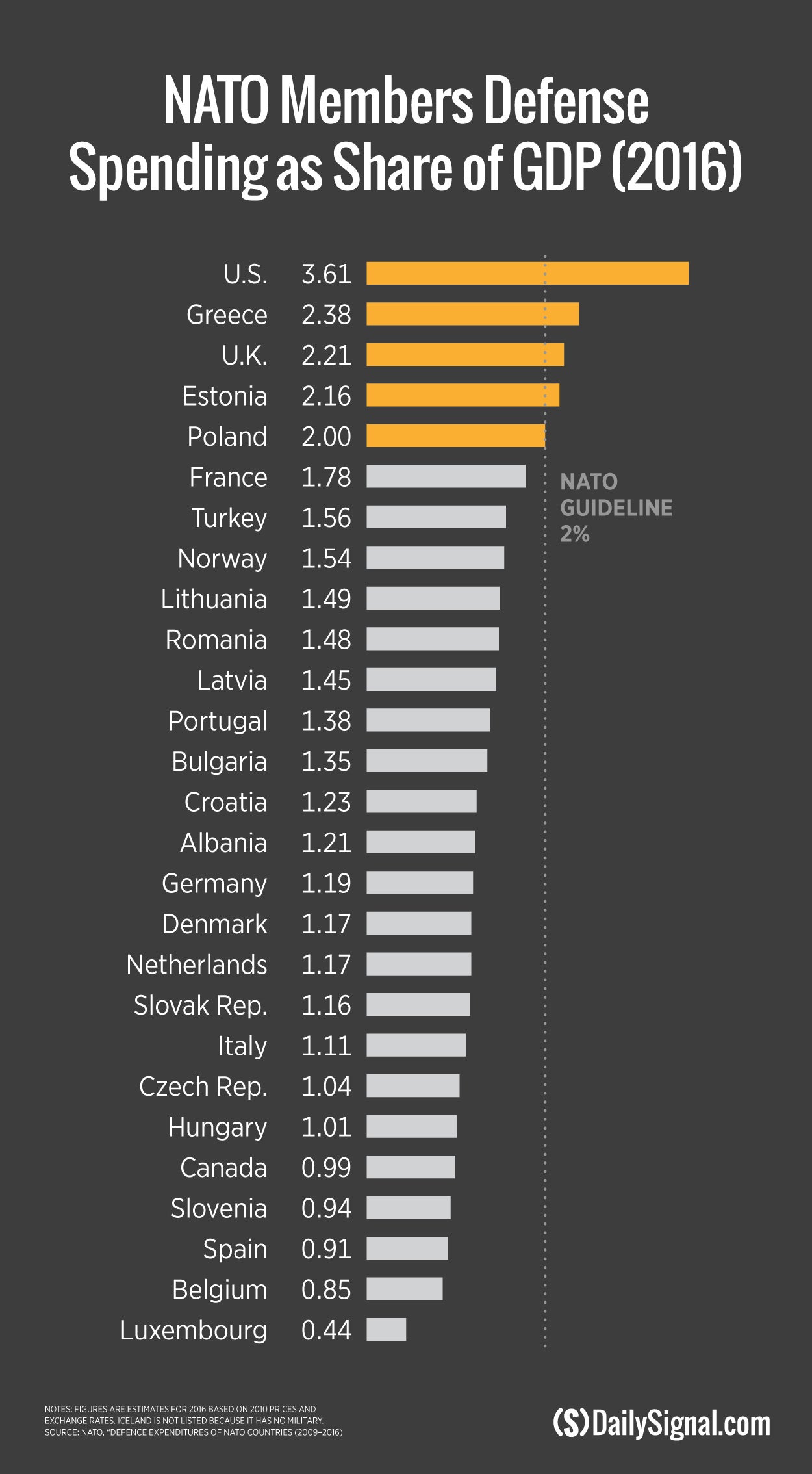

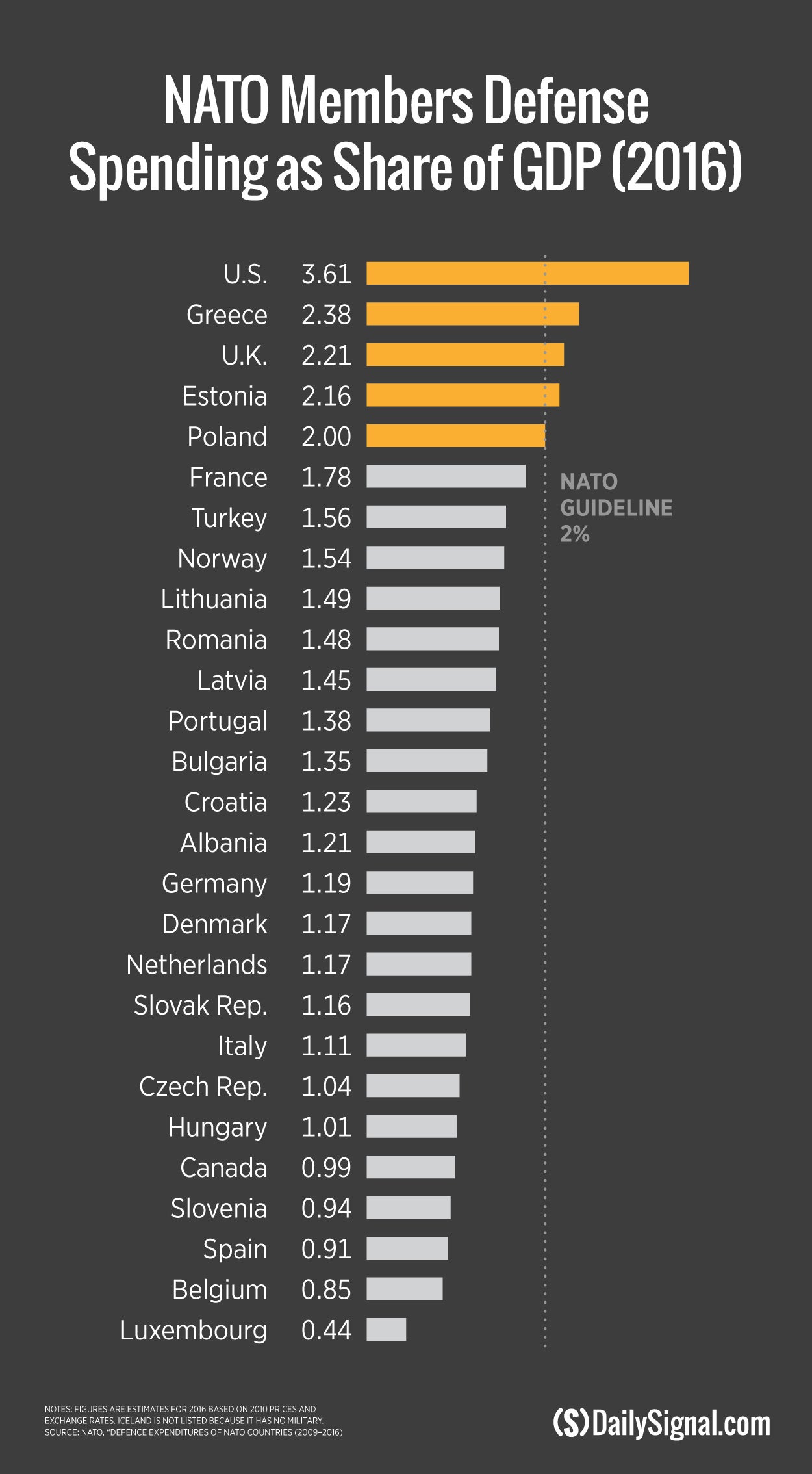

Currently, only five of NATO’s 28 members—the U.S., Greece, Britain, Estonia, and Poland—meet the alliance’s target of spending at least 2 percent of their own gross domestic product on defense, a fact that is especially concerning, experts say, because of Russia’s aggressive behavior.

While the alliance increased overall defense spending in 2015 for the first time in two decades, the U.S. continues to be overwhelmingly the largest contributor, committing 3.61 percent of its GDP. The U.S. spends nearly three times as much as all European members of NATO combined.

The second-highest military spender based on a share of its GDP is Greece, at 2.38 percent.

“This has been a demand from the U.S. for a long time, except now there is a new sheriff in town and his using of words is just different,” said Andras Simonyi, a former Hungarian ambassador to both the U.S. and NATO, in an interview with The Daily Signal. “The choice of words may not be good, but if the Europeans think they can continue to live in a dream world where the U.S. is the ultimate protector, and Europe isn’t really doing as much as it should or could to defend itself, there will come a point where the U.S. says enough is enough.”

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, better known as NATO, is a political-military alliance founded in 1949 comprised of the U.S. and mostly European countries.

Originally designed to protect the territorial integrity of its neighbors and defend Western Europe from the Soviet Union, the alliance has more recently played an important role assisting in the fight against terrorism.

In an interview published just days before he was sworn into office, Trump told the German newspaper Bild and The Times of London that NATO is “obsolete” and “very unfair to the United States.” He said that most nations don’t meet their spending commitments, before adding, “with that being said, NATO is very important to me.”

During the campaign, Trump said he would first look at countries’ contributions to the alliance before deciding whether to automatically defend NATO members if they are attacked—putting into question his commitment to the alliance’s founding treaty, which states that an attack on one member is an attack on all members.

That promise has been invoked only once, in response to the 9/11 attacks.

Daniel Kochis, a policy analyst in European affairs at The Heritage Foundation, says Trump would be unwise to condition the U.S. defense of its allies and said there are other ways to encourage NATO countries to spend more.

Kochis recommends that the Trump administration push member countries to embed a commitment to spend 2 percent of GDP on defense into their own legislation, to make governments more accountable to reach the benchmark.

He also said the U.S. should encourage the creation of a special session for finance ministers at NATO summits, where countries’ financial leaders could meet and come to appreciate “why defense spending is important.”

“Trying to find innovative ways to get folks in Europe to spend more on defense is fine, but the president should not go as far to say we won’t be there for our allies,” Kochis told The Daily Signal. “We need to be clear the U.S. is still committed to NATO.”

Seeking to reassure allies, James Mattis, on his first working day as Trump’s secretary of defense on Monday, called NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to underscore the “importance he places on the alliance,” a Pentagon spokesperson told the media in a statement.

In his confirmation hearing before the Senate, Mattis warned that Russia is out to “break the North Atlantic alliance” and that U.S. and European countries must strengthen their ties.

Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, a territory of Ukraine, in 2014, many NATO members are worried about protecting their territory from Russian expansion and influence, especially the small Baltic states that are among the more recent entrants to the alliance: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

This threat perception has inspired members to spend more on defense. Former President Barack Obama and his secretary of state, John Kerry, had long called on their NATO allies to pay their “fair share.”

In 2014, NATO leaders came to an agreement that members who spend under that 2 percent benchmark are to work toward reaching that goal within a decade.

Michael O’Hanlon, a defense and foreign policy expert at the Brookings Institution, says that while there is “certainly a free rider problem” within NATO, the alliance combined to contribute about half the world’s military spending.

He said several countries, especially in southern Europe, do not see Russia as much of a threat like those located closer to the Kremlin do, and that many of these nations, like Spain and Italy, are still recovering from the 2008 financial crisis and can’t afford to spend more on defense.

But as countries begin to increase their spending, O’Hanlon says the Trump administration should harness that momentum and encourage allies to continue to move in that direction, rather than hedge on the U.S. commitment to NATO.

“Trump is half right that they do rely on the U.S. and are a bit spoiled by the fact we have their backs,” O’Hanlon told The Daily Signal in an interview. “But we don’t want to talk down our commitment to NATO because there really is fair amount of capability. We may not be getting what we want, but NATO is still the most valuable security relationship that the U.S. has in the world.”

Currently, only five of NATO’s 28 members—the U.S., Greece, Britain, Estonia, and Poland—meet the alliance’s target of spending at least 2 percent of their own gross domestic product on defense, a fact that is especially concerning, experts say, because of Russia’s aggressive behavior.

While the alliance increased overall defense spending in 2015 for the first time in two decades, the U.S. continues to be overwhelmingly the largest contributor, committing 3.61 percent of its GDP. The U.S. spends nearly three times as much as all European members of NATO combined.

The second-highest military spender based on a share of its GDP is Greece, at 2.38 percent.

“This has been a demand from the U.S. for a long time, except now there is a new sheriff in town and his using of words is just different,” said Andras Simonyi, a former Hungarian ambassador to both the U.S. and NATO, in an interview with The Daily Signal. “The choice of words may not be good, but if the Europeans think they can continue to live in a dream world where the U.S. is the ultimate protector, and Europe isn’t really doing as much as it should or could to defend itself, there will come a point where the U.S. says enough is enough.”

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, better known as NATO, is a political-military alliance founded in 1949 comprised of the U.S. and mostly European countries.

Originally designed to protect the territorial integrity of its neighbors and defend Western Europe from the Soviet Union, the alliance has more recently played an important role assisting in the fight against terrorism.

In an interview published just days before he was sworn into office, Trump told the German newspaper Bild and The Times of London that NATO is “obsolete” and “very unfair to the United States.” He said that most nations don’t meet their spending commitments, before adding, “with that being said, NATO is very important to me.”

During the campaign, Trump said he would first look at countries’ contributions to the alliance before deciding whether to automatically defend NATO members if they are attacked—putting into question his commitment to the alliance’s founding treaty, which states that an attack on one member is an attack on all members.

That promise has been invoked only once, in response to the 9/11 attacks.

Daniel Kochis, a policy analyst in European affairs at The Heritage Foundation, says Trump would be unwise to condition the U.S. defense of its allies and said there are other ways to encourage NATO countries to spend more.

Kochis recommends that the Trump administration push member countries to embed a commitment to spend 2 percent of GDP on defense into their own legislation, to make governments more accountable to reach the benchmark.

He also said the U.S. should encourage the creation of a special session for finance ministers at NATO summits, where countries’ financial leaders could meet and come to appreciate “why defense spending is important.”

“Trying to find innovative ways to get folks in Europe to spend more on defense is fine, but the president should not go as far to say we won’t be there for our allies,” Kochis told The Daily Signal. “We need to be clear the U.S. is still committed to NATO.”

Seeking to reassure allies, James Mattis, on his first working day as Trump’s secretary of defense on Monday, called NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to underscore the “importance he places on the alliance,” a Pentagon spokesperson told the media in a statement.

In his confirmation hearing before the Senate, Mattis warned that Russia is out to “break the North Atlantic alliance” and that U.S. and European countries must strengthen their ties.

Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, a territory of Ukraine, in 2014, many NATO members are worried about protecting their territory from Russian expansion and influence, especially the small Baltic states that are among the more recent entrants to the alliance: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

This threat perception has inspired members to spend more on defense. Former President Barack Obama and his secretary of state, John Kerry, had long called on their NATO allies to pay their “fair share.”

In 2014, NATO leaders came to an agreement that members who spend under that 2 percent benchmark are to work toward reaching that goal within a decade.

Michael O’Hanlon, a defense and foreign policy expert at the Brookings Institution, says that while there is “certainly a free rider problem” within NATO, the alliance combined to contribute about half the world’s military spending.

He said several countries, especially in southern Europe, do not see Russia as much of a threat like those located closer to the Kremlin do, and that many of these nations, like Spain and Italy, are still recovering from the 2008 financial crisis and can’t afford to spend more on defense.

But as countries begin to increase their spending, O’Hanlon says the Trump administration should harness that momentum and encourage allies to continue to move in that direction, rather than hedge on the U.S. commitment to NATO.

“Trump is half right that they do rely on the U.S. and are a bit spoiled by the fact we have their backs,” O’Hanlon told The Daily Signal in an interview. “But we don’t want to talk down our commitment to NATO because there really is fair amount of capability. We may not be getting what we want, but NATO is still the most valuable security relationship that the U.S. has in the world.”

No comments:

Post a Comment