In 2008, PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel gave half a

million dollars to a Google engineer named Patri Friedman, the grandson

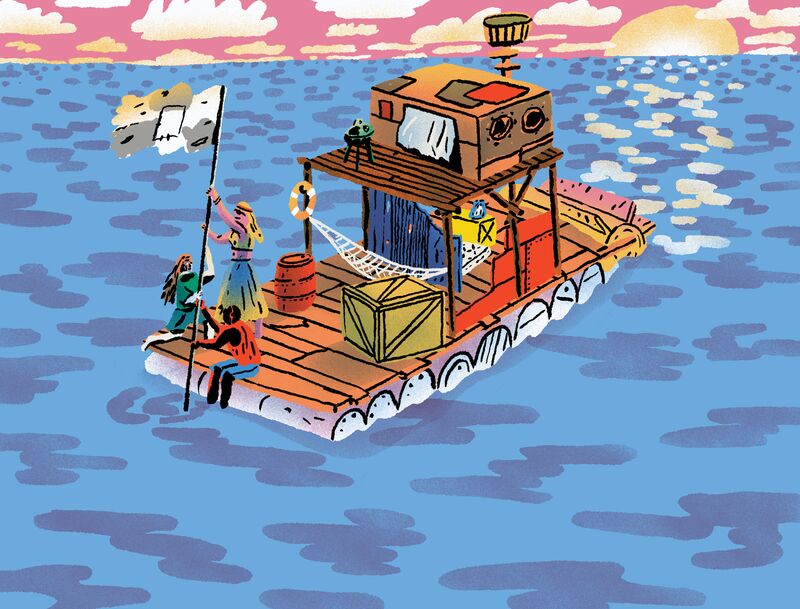

of economist Milton Friedman. The money was to establish the Seasteading

Institute, which aims to spearhead the development of politically

autonomous, floating “seasteads” in unregulated international waters.

This was to be the beginning of a long experiment in civilization

building. It also turned out to be the origin of many, many puns.

Nearly a decade in, this experiment has yielded more theory than practice. Nevertheless, the institute has published a wildly optimistic book called Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity From Politicians. Written by staff “aquapreneur” Joe Quirk, with an assist from Friedman, Seasteading’s principal argument is that “the world needs a Silicon Valley of the sea, where those who wish to experiment with building new societies can go to demonstrate their ideas in practice.”

The dream of oceanic colonization is at least as old as science fiction, but the institute is both contemporary and sincere. The book begins by heralding 2050 as a “deadly deadline: an approaching pinch point in the supply of several key commodities that humanity needs to survive.” By then, Quirk and Friedman warn, more than half the world’s population will lack fresh water, and we’ll have reached “peak phosphorous,” when we no longer have enough of the mineral, which is key to agricultural production, to feed ourselves.

For every problem the book raises, seasteading is the solution. “Imagine”—lots of sentences begin with that word—“if we didn’t have to wait for the caprice of political history to create Hong Kongs and Singapores.” (Hong Kong counts as a “pre-stead.”) While critics envision seasteads as glorified tax havens for the rich, proponents contend that mobile, modular colonies represent humanity’s last best hope—be it for testing new modes of governance or combating the rising tide of climate change.

Seasteading goes to great lengths to convince us that free-floating cities aren’t as far-fetched as they sound, and in some respects, it succeeds. What are cruise ships, Quirk and Friedman ask, if not prototypical seasteads? They tout the brawniness of a liquefied natural gas platform built by Shell to withstand a Category 5 typhoon. They salivate over the idea of a carbon-neutral skyscraper made of magnesium harvested from seawater (aka “seament” or “seacrete”). But if you’re expecting Seasteading to pay more than scant attention to, say, the cruise industry’s checkered record on workers’ rights, it will disappoint you. Quirk and Friedman’s techno-libertarian self-certainty runs deep.

Along the way, the writers regale us with “bluetopian” proposals from marine biologists, nautical engineers, a feminist “shesteader,” and Titanic co-discoverer Robert Ballard, who recounts the time he went mano a mano with Buzz Aldrin over space vs. sea colonization during a National Geographic TV special. (“I really took off the gloves and told the astronauts that populating Mars was a crock of shit.”)

Nearly a decade in, this experiment has yielded more theory than practice. Nevertheless, the institute has published a wildly optimistic book called Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity From Politicians. Written by staff “aquapreneur” Joe Quirk, with an assist from Friedman, Seasteading’s principal argument is that “the world needs a Silicon Valley of the sea, where those who wish to experiment with building new societies can go to demonstrate their ideas in practice.”

The dream of oceanic colonization is at least as old as science fiction, but the institute is both contemporary and sincere. The book begins by heralding 2050 as a “deadly deadline: an approaching pinch point in the supply of several key commodities that humanity needs to survive.” By then, Quirk and Friedman warn, more than half the world’s population will lack fresh water, and we’ll have reached “peak phosphorous,” when we no longer have enough of the mineral, which is key to agricultural production, to feed ourselves.

For every problem the book raises, seasteading is the solution. “Imagine”—lots of sentences begin with that word—“if we didn’t have to wait for the caprice of political history to create Hong Kongs and Singapores.” (Hong Kong counts as a “pre-stead.”) While critics envision seasteads as glorified tax havens for the rich, proponents contend that mobile, modular colonies represent humanity’s last best hope—be it for testing new modes of governance or combating the rising tide of climate change.

Seasteading goes to great lengths to convince us that free-floating cities aren’t as far-fetched as they sound, and in some respects, it succeeds. What are cruise ships, Quirk and Friedman ask, if not prototypical seasteads? They tout the brawniness of a liquefied natural gas platform built by Shell to withstand a Category 5 typhoon. They salivate over the idea of a carbon-neutral skyscraper made of magnesium harvested from seawater (aka “seament” or “seacrete”). But if you’re expecting Seasteading to pay more than scant attention to, say, the cruise industry’s checkered record on workers’ rights, it will disappoint you. Quirk and Friedman’s techno-libertarian self-certainty runs deep.

Along the way, the writers regale us with “bluetopian” proposals from marine biologists, nautical engineers, a feminist “shesteader,” and Titanic co-discoverer Robert Ballard, who recounts the time he went mano a mano with Buzz Aldrin over space vs. sea colonization during a National Geographic TV special. (“I really took off the gloves and told the astronauts that populating Mars was a crock of shit.”)

Meanwhile, this year’s Ephemerisle is set for July. A reality-TV production company once expressed interest in doing a series on the gathering, but Quirk and Friedman proudly report there just wasn’t enough conflict to make it work. This, of course, proves their point. “If you want people to fight,” they write, “condemn them to a crowded space where they can’t take their land and go elsewhere.”

No comments:

Post a Comment