The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization, by Arthur Herman. New York: Random House, 2013. 704 pp. $13.99 (Kindle).

Arthur Herman’s The Cave and the Light

is more than a history; it is an enlightening drama. It is not a novel,

but it often reads like one. As Herman puts it, “This is neither a

history of philosophy nor a history of Western civilization. It is an

account of the interaction of both, and of how the legacies of Plato and

Aristotle live on around us and continue to shape our world” (loc. 51).Herman has not merely summarized dense treatises. He has brought their authors and those who have carried on their ideas to life. I disagree strongly with some aspects of Herman’s analysis, yet I found the book (particularly the Audible version) thrilling and educational.

The subtitle of the book is Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization. “This book,” Herman says, “tells the story of how everything we say, do, and see has been shaped in one way or another by two classical Greek thinkers, Plato and Aristotle. . . . And at the center of their influence has been a two-thousand-year struggle for the soul of Western Civilization, which today extends to all civilizations” (loc. 25). It is refreshing to read a work that recognizes and conveys the role of fundamental philosophical ideas in shaping history, particularly amid the chorus of modern philosophers who treat the subject as though it were a game of words.

The

greatest virtue of this book, and what makes it particularly enjoyable,

is that Herman spares no effort in painting a rich, detailed, and

imaginative picture of his subjects. And although the main subjects of

the book are Plato and Aristotle, they are not the only subjects. Here,

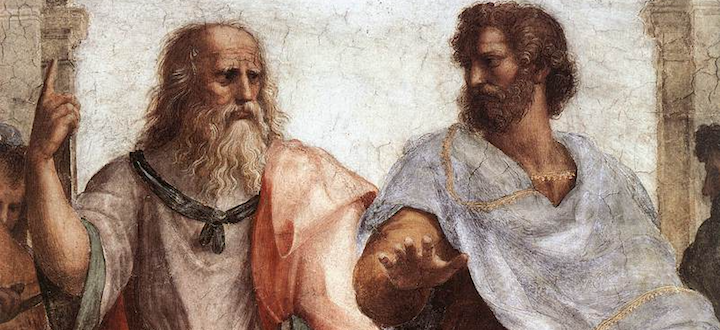

for instance, is how Herman indicates the genesis of Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, which adorns the book’s cover. After providing relevant historical context regarding Pope Julius II’s reign, Herman writes:

The

greatest virtue of this book, and what makes it particularly enjoyable,

is that Herman spares no effort in painting a rich, detailed, and

imaginative picture of his subjects. And although the main subjects of

the book are Plato and Aristotle, they are not the only subjects. Here,

for instance, is how Herman indicates the genesis of Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, which adorns the book’s cover. After providing relevant historical context regarding Pope Julius II’s reign, Herman writes:So at some point in the winter of 1508, he [the pope] and Raphael and Bramante would have wandered inside, passing teams of artists and assistants laboring in the halls with paintbrushes and trowels. They would have seen their breath as they stood in the frigid air. Their words would have echoed in that soaring empty space. “This shall be our personal library,” Julius probably said, gesturing toward the empty walls. “Give us a design suited to that purpose.” (loc. 123)Herman acknowledges that we cannot know exactly what happened or what was said. But he artfully combines knowledge and imagination to fill in the gaps and bring the story to life.

The book is as heavy on facts and analysis as it is on fantasy and imagination. Herman offers incisive analysis of Plato’s and Aristotle’s works and ideas (as well as those of some major successors). For instance, he delves into the Timaeus, Plato’s creation myth, where we learn about how an immaterial god created the universe by using numerically modeled perfect Forms to shape an imperfect material world and all its objects. According to Plato, the abstract and immaterial creates the concrete and material; the “Forms,” as he calls the former, are primary and thus more important than the latter.

Herman later details how the early Christians usurped huge swaths of the Timaeus and wove it into their religion. “Today, historians point to social and economic factors to explain Christianity’s amazing spread. But the key factor was its skill in seizing the high ground of Greek thought, especially Plato” (loc. 2861). . . .

No comments:

Post a Comment