Chavez's Chickens Come Home to Roost

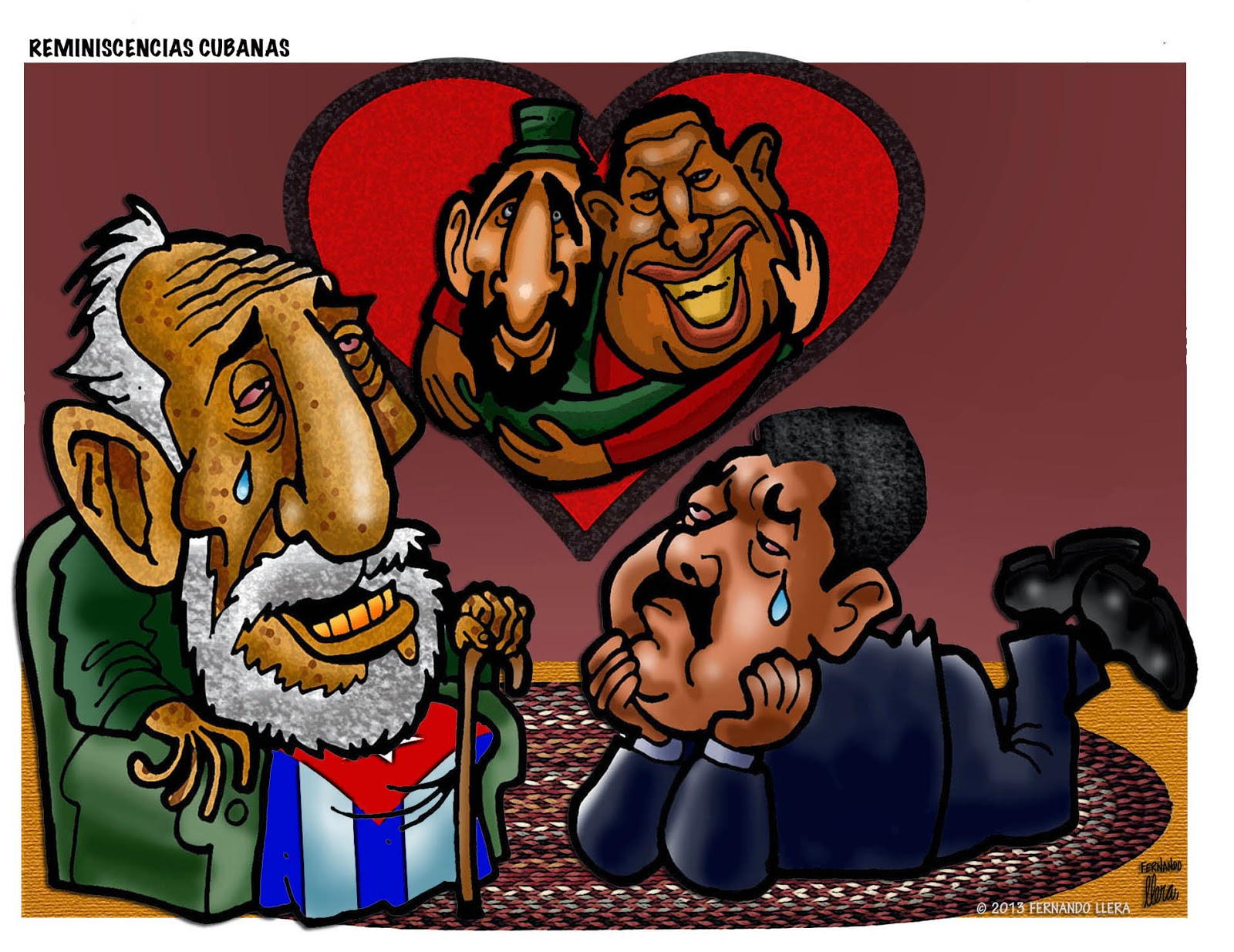

Hugo Chavez and his successor, Nicolas Maduro, have controlled the oil-rich nation for nearly 20 years now. And, under their banner of “Socialism of the 21st Century,” they have marched their people straight into economic and political bankruptcy.

Last year, the collapse in global oil prices brought Venezuela’s already floundering economy to its knees. The International Monetary Fund estimates that while that the economy contracted 10 percent last year, even as inflation hit 275 percent. This year, the IMF predicts, will be much worse.

Today, the bolivar is virtually worthless; food is in short supply and crime continues to worsen. The backlash against the ruling United Socialist Party (PSUV) has been strong. Last December, for the first time in 17 years, the country’s democratic opposition won a majority in the National Assembly.

How did things go so horribly wrong? Early in Chavez’s reign, soaring oil prices gave him the resources to fund a massively corrupt welfare state. Absurd social programs and direct cash transfers ensured PSUV loyalty from the nation’s poor, even as top officials embezzled untold billions. One of Chavez’s daughters, for instance, is reported to have more than $4 billion stashed in foreign banks.

In establishing his kleptocracy, Chavez destroyed what had been the foundation of Venezuelan prosperity: democracy, economic freedom, and the rule of law. These three conditions are synergistic.

For the last 21 years, The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal have published an annual Index of Economic Freedom, assessing the degree of economic freedom in over 175 nations. During that period, Venezuela’s score has dropped more than any other nation’s, plummeting from 59.8 to 33.7. Only two other countries — Cuba and North Korea — now rate worse. The intrinsic link between economic freedom and prosperity cannot be denied.

Despite the clear need for change, the PSUV is resisting any meaningful attempt to liberalize its economy. The biggest reform it has announced to date is a reluctant reduction in the state’s enormous subsidy of gas prices. The reduction, to $10 billion from $12 billion annually, may seem significant. Yet when measured against the countries financial woes — including the $10.5 billion foreign debt payments due throughout the year — the move seems little more than symbolic.

Nor are they accepting of the Venezuelan people’s demand for change. In a country with traditionally high levels of voter-absenteeism, a historic 75 percent of Venezuelan voters participated in the legislative elections of Dec. 6. The opposition coalition obtained 67 percent of the popular vote, in spite of countless electoral abuses by the ruling party.

Still, the coalition has faced an uphill battle to exercise its popular and constitutional mandate. A hostile judicial branch, acting on behalf of Mr. Maduro, has blocked its efforts. The constitutional crisis sparked by these standoffs has paralyzed the government during the country’s worst economic crisis in modern history.

The PSUV is not the only problem the coalition faces. It must also deal with significant challenges from within. The coalition consists of numerous parties from across the ideological spectrum. Their single common bond is opposition to the socialist regime.

Maintaining unity among parties with very different — and often competing — interests is as difficult as it is essential, if the coalition is to bring meaningful improvement to the lives of their constituents. Yet unity has remained elusive and appears less likely every day. At its core, the coalition does not currently represent a viable political alternative.

Last year, the bolivar was worth less than a penny on the popular market. With inflation expected to leap to 720 percent, the currency’s value will continue to drop and the desperation of the Venezuelan people will rise. Loyalty to the socialist party will be tested in the face of increased food and household good shortages. The worst is yet to come for Venezuela’s state-sponsored economic crisis.

- Ana Quintana is a policy analyst specializing in Latin America and the Western Hemisphere.

No comments:

Post a Comment